A Stochastic Estimation of Pi

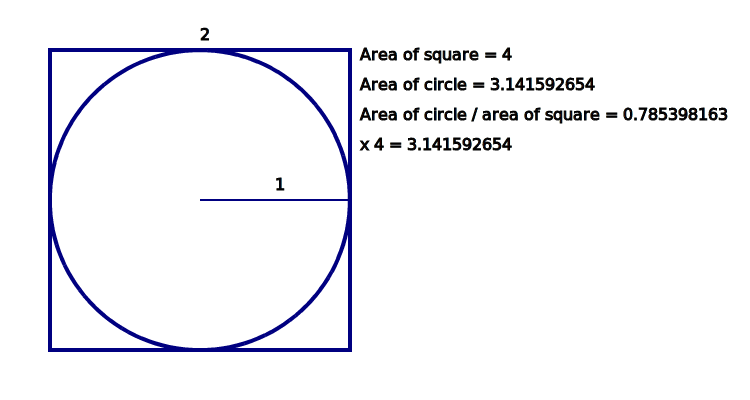

The graphic below shows a square with sides of length 2 containing a circle with a radius of 1. The area of the square is 4 and the area of the circle is 3.141592654 (sound familiar?!). The ratio of the area of the circle to the area of the square is 0.785398163 which is π / 4.

A while ago I wrote an article on estimating pi using various formulae, and in this post I will use the circle-within-a-square ratio illustrated above to run a stochastic simulation in Python to estimate a value of π.

Stochastics

The word stochastic comes from the Greek meaning "to aim at a target", but in general modern usage refers to simulations using random variables.

Such simulations are widely used in many fields from economics to meteorology, including many areas which fall into the category of artificial intelligence and machine learning. The general principle behind stochastics is that it is impossible to accurately capture and model complex systems with vast numbers of data points, but using appropriate random data we can model a simulated system which, by the "law of averages" will closely match the real world. If it does not then the model and/or method of generating random values can be tweaked.

For this project I will combine the "aim at a target" and "simulation using random variables" meanings of stochastic to simulate firing a large number of arrows at the square in the graphic above. If we keep a count of the proportion of arrows which land in the circle this should be somewhere in the region of 0.785398163. When our virtual quiver is empty we can multiply the ratio we end up with by 4 to get an estimation of π.

This is not of course the best way of estimating pi and using it to do so is frankly overkill. However, it does give a simple introduction into the principle of using random variables in a simulation.

Coding

This project consists of a single file called stochasticpi.py which you can clone or download from the Github repository.

import random

import math

def main():

print("-----------------")

print("| codedrome.com |")

print("| Stochastic Pi |")

print("-----------------\n")

start(10_000_000, 1_000_000)

def start(arrow_count: int, output_interval: int):

"""

Simulate firing arrows at a circle within a square, the proportion hitting

the circle being used to estimate a value for Pi.

"""

arrows_fired = 0

circle_hits = 0

pi_estimate = 0

x = 0

y = 0

for i in range(0, arrow_count):

x = random.uniform(-1, 1)

y = random.uniform(-1, 1)

arrows_fired += 1

if _in_unit_circle(x, y):

circle_hits += 1

pi_estimate = (circle_hits / arrows_fired) * 4

if arrows_fired % output_interval == 0:

print(f"Intermediate estimate of Pi after {arrows_fired:,d} arrows: {pi_estimate:.16f}")

print(f"Final estimate of Pi after {arrow_count:,d} arrows: {pi_estimate:.16f}")

def _in_unit_circle(x: float, y: float):

"""

Calculate whether a particular position within a square

is within a circle fitting the square.

"""

if math.sqrt(x**2 + y**2) <= 1:

return True

else:

return False

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()At the top of the file we import random and math, and then comes the main function which simply calls start.

In the start function we first set up a few variables, all initialized to 0, and then enter a loop from 0 to the number of iterations. Firing an arrow is simulated by setting x and y to random values between -1 and 1. (This assumes the centre of the square is 0,0.) We then call a separate function to check if the arrow hit the circle; if so circle_hits is incremented. We then update the estimate of pi. At the end of the loop we check if the current iteration is a multiple of the output interval; if so we print the estimate arrived at so far. This process slows everything down a lot so if you are just interested in the end result you could remove it as well as the output_interval argument. If you do then you will only need to calculate pi_estimate once at the end.

The process of checking whether an arrow has hit the circle is carried out by a separate function called _in_unit_circle. This uses the old "square on the hypotenuse is equal to...", the values of x and y being "the other two sides" and the line from the centre of the circle to x,y being the hypotenuse. If the hypotenuse is <= 1 then the point is inside the circle, otherwise it is outside.

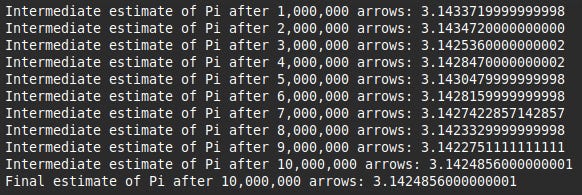

Now let’s run the program with python3 stochasticpy.py. The output is:

Every run will be different and in this run I only got 2dp of accuracy despite using a million arrows. However, the purpose of this post was to demonstrate a technique rather than develop a practical solution.

No AI was used in the creation of the code, text or images in this article.